Ohio’s Sustainable Future: Taking the Lead in Transit and Zoning Part 1: Cincinnati

Public transportation is booming across the country. In the Midwest, cities like Cleveland, Grand Rapids, and Minneapolis – St. Paul have had Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) for years. Now, Cincinnati and Columbus are following suit, with both cities approving new BRT systems within the last two years.

Some of this progress is fueled by the bipartisan infrastructure bill of 2021, which marked the largest public transit investment in U.S. history. From this, Amtrak has launched studies for 6 potential routes in Ohio alone, offering much-needed alternatives to current car-dependent intracity travel. According to Greater Ohio Policy Center, “Columbus and Cincinnati each experienced .5% growth between 2022-2023, with both cities outpacing the .2% growth of the state as a whole and .49% national growth rate.” As cities in Ohio grow, connection through passenger rail will erupt with new opportunities and boost local business through connectivity. These developments will bring economic benefits and drive development in their surrounding communities.

Cincinnati is going through a momentous period with coinciding progress being made on public transportation, zoning reform, and tax abatements for new residential developments. We took a look at where these three seemingly independent maneuvers overlap. Cincinnati is an ideal case study looking through the lenses of new BRT routes well underway, recently passed zoning reform, and tax abatements for affordable and sustainable housing.

What is BRT?

BRT, or Bus Rapid Transit, is different from the typical bus system in that it achieves higher capacity with faster and more reliable service. To attain this, the system is designed with dedicated bus-only lanes, stations, and right of way. Essentially, BRT operates as light rail, but at a cheaper upfront cost. Buses are given signal priority, and arrive at any given station within 15 minutes.

Thanks to the passage of Issue 7 in 2020, Cincinnati is introducing its first two BRT corridors: Hamilton Avenue and Reading Road. This plan includes the use of the Riverfront Transit Center below 2nd Street, which was originally built in 2003 during the Fort Washington Way reconstruction. Since then, it has primarily sat empty. This rehabilitation effort is one reason why this plan is so exciting, as it is bringing life back to an existing facility, with minimal investment. Construction on these corridors starts in 2026, with station locations currently being finalized through public input, and are expected to begin service in 2027 for Hamilton Avenue and 2028 for Reading Road. By connecting neighborhoods and reducing car dependency, BRT expands mobility options while enhancing economic development opportunities in adjacent areas.

Connected Communities Zoning Reform

Alongside the new BRT routes, effective July 1, 2024, Cincinnati’s “Connected Communities” zoning reform is aimed at fixing “the missing middle”, Essentially, the Cincinnati metro area has a shortage of roughly 50,000 affordable rental units, which can also be referred to as “middle housing” that comes in the form of multiunit structures. The new zoning reform aims to allow for more density in select zoning areas, and eliminates parking minimums in specific areas.

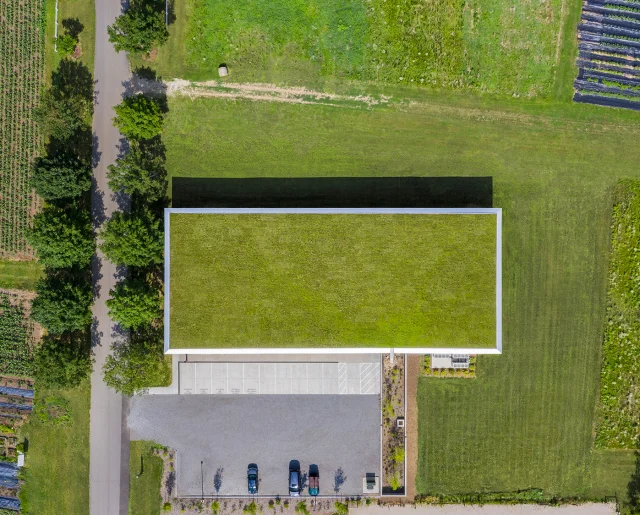

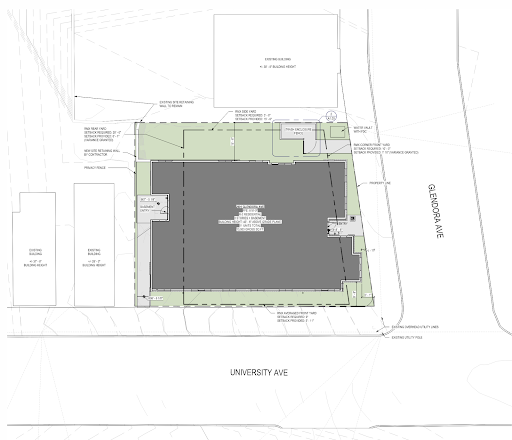

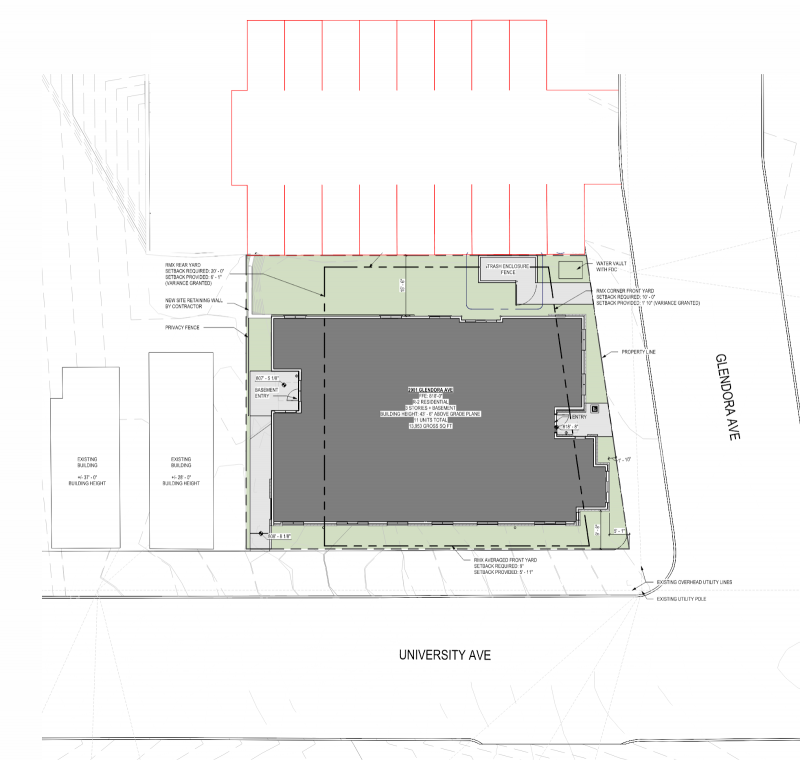

For an example of how this reform makes a difference, let’s look at one of our projects, University and Glendora. The site currently consists of a detached garage, an under-utilized retail space with an apartment above, and a parking lot for 10 cars. Our client, having done many projects in the area for student housing, strategically chose this site with the incoming Connected Communities policy to maximize units.

Being one block from the University of Cincinnati, this was the perfect location for a project of this density. The building provides 11 multi bedroom apartments, but there is little need for the corresponding parking that is typically desired by residents if this building were placed in, say, Oakley or Walnut Hills. It is not necessary for college students to have a car on campus as they can walk to school and the nearby Kroger, especially with the incoming BRT system that will swiftly get students downtown via two new routes with service every 10-15 minutes. In the future, with expanded Amtrak service, students who live out of town can take the train home for holiday breaks. Take a look at the pictures below to see the difference between what was previously permittable without any variances vs what is now allowed under connected communities.

Before: RMX (Residential Mixed) | Allowed: Max Height: 35 ft | Min Lot Area per dwelling: 2,500 sf | Parking: 1.5 for every unit

After: RMX-T (Residential Mixed – Transportation) | Allowed: Max Height: 47 ft | Min Lot Area per dwelling: none | Parking: none

MA’s Design, taking advantage of Connected Communities

If parking were required – 17 spaces for 11 units

It’s not to say that this development could not have been made prior to the passing of Connected Communities, but it undoubtedly would have taken more time to be approved. As the saying goes, “time is money” and developers are aware applying for variances takes a large effort, justification, and most importantly time. Connected Communities moves the baseline, and makes the case that there are corridors in Cincinnati that have been craving more dense development. Where you may have only been allowed to build a single family house before, you can now build a duplex, triplex, quadplex, townhomes and more. This is called “middle housing”, or often referred to as the “missing middle”.

To give a summarized history lesson: in the 1940s to 1960s, after World War II, there was a large movement to the suburbs, also referred to as white flight. The GI Bill provided money to veterans, often used to purchase houses in the suburbs, and zoning laws changed to allow only single-family homes to be built. This also included racist policies like redlining and blockbusting, which inherently removed Black families from neighborhoods. You can see the effects of the single-family zoning trend as you drive through Cincinnati neighborhoods like Hyde Park, where some multi-unit structures that were grandfathered in still exist, but are decades old.

The University and Glendora project is an ideal case study for other areas in Cincinnati to use for precedent demonstrating how zoning reform and transit improvements work together to enable sustainable urban living. The benefits to reducing single passenger vehicles are long: from reducing traffic congestion, less air pollution, improved personal health from exercise, and much more.

Tax Abatements for Residential Properties

With old housing stock in many neighborhoods in Cincinnati that often have properties in disarray, tax abatement programs can help incentivize restoration projects or new buildings on empty lots. Both can help densify a neighborhood especially considering the benefits of BRT and zoning changes mentioned above.

Abatement is a tool that a city or jurisdiction can use to eliminate or lower property taxes for a period of time to incentivize development in a specific area, or a specific type of development. When a homeowner makes upgrades to their property, the property value increases and, thus, property taxes increase. This can be a barrier to middle and low income residents building new homes or renovating their existing homes. This program allows those homeowners to pay taxes on the pre-improvement value of the property for up to 15 years. This is all done to encourage development that will put new life into the housing supply and retain residents.

Cincinnati’s updated tax abatement program incentivizes housing renovations and new construction, with additional bonuses for LEED certification, meeting universal design standards, historic restoration, and transit-friendly developments. By offering greater abatements in lower-income neighborhoods, the program fosters equitable growth while encouraging dense, sustainable housing in transit corridors. These bonuses can also be stacked for up to $300,000 in abated value.

WVXU provides a great example, a new constructed house in East Walnut Hills would qualify for the following abatements

In an Expand neighborhood: 10 years, $300,000 max abated new value

Missing middle bonus: $75,000 (for 2 units)

Visitability and Universal Design: $50,000

Total: $425,000 maximum abated increase in market improvement value

Essentially, the value of the land can be improved by $425,000 (by meeting the standards) or less, and no additional property taxes will be billed for 10 years. The homeowner will continue to pay the property tax of the original value, but this can be a savings of thousands of dollars when considering the additional value of a renovation or new build. Once the allotted time is up, the homeowner will pay the taxes on the full value of the property. If you would like to read more about Cincinnati’s tax abatement program please follow this link.

What does it mean all together?

Cincinnati’s combined focus on public transit, zoning reform, and equitable tax incentives demonstrates how cities can integrate mobility and density to drive development. These initiatives serve as a blueprint for sustainable urban growth, benefiting residents, businesses, and communities.

As architects, we are excited to contribute to projects that align with these transformative changes. By designing for density and connectivity, we can help shape the vibrant, transit-oriented communities of the future.

As cities in Ohio continue to grow, from climate migration (see Green Cincinnati Plan) and investment made by individual companies, (see article from the Columbus Dispatch) Cincinnati will no doubt be used as a case study to show an impactful way of integrating mobility and density to allow for better growth.

The maps below show how the BRT routes, connected communities, and tax abatement zones overlay, and where development will be realized in the future. These areas will need to be continually studied to see how development actually grows through the city, but can also project where new transportation should be laid to continually connect communities.